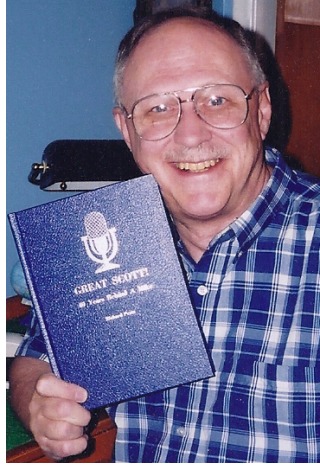

GREAT SCOTT! 40 Years Behind A Mike

GREAT SCOTT! 40 Years Behind A Mike

By Richard (Dick Scott) Pratz

Soon after retiring, Richard wrote and self-published a book about his career, "GREAT SCOTT! 40 Years Behind A Mike". Two chronological chapters dedicated to his time in Sudbury are included here. Richard's chapters are filled with his personal thoughts and observations upon moving to the Sudbury area from Chicago, Illinois as a vital step in his broadcast career. Richard regards his years at CKSO as some of the happiest in the business. He also attributes much of his knowledge and experience from his work at CKSO AM, FM and Television. From anchoring morning radio news, playing the part of several fictious, funny characters with Michael Cranston and Paul Burke throughout the CKSO AM Radio morning shows, to hosting classical music programs, serving as television chief announcer and hosting a weeknight television talk show, he acquired the kind of knowledge and experience one can only get from doing. Richard’s chapters provide an inside look at what his typical day was like and they serve as a timestamp with historical reflections of radio and television in Sudbury in the early 1970s. The following two chapters, “The Great White North” and “Tonite not Tonight” are reprinted, word for word, with Richard’s blessing.

CHAPTER: The Great White North

I shall always remember the day I announced to my parents I was leaving the United States for a new life in Canada. Not wishing to break the news over the telephone, I drove to their apartment at 2214 Argyle to explain why I had chosen this path. They were heartbroken and tried to talk me out of it. But my back was against the wall. I was unable to find employment in the U.S. and I had found a Canadian station that welcomed me with open arms. All my mother and father could see, however, was they were losing their baby boy to a strange and far-off land where opportunities to visit would be fewer. After we said our farewells inside the home where I grew up, my father accompanied me outdoors to my car. My mother couldn’t bear what she perceived at that time as a ‘final goodbye’ and remained inside crying. As close as my father had been to his two sons, he had never been a demonstrative man. Shaking hands, a playful whack on the butt or a brief hug was about all he could bring himself to do. But this time it was different. I don’t recall who made the first move to embrace the other, but we stood curbside on that tree-lined Chicago street for the longest time hugging each other, crying, and not wanting to let go. It was a very emotional big deal to both of us. It was to be the only long and lasting embrace I would ever receive from my father in what turned out to be the last three years of his life. Despite being so apart geographically, we did visit each other before he passed away in 1972. These visits also continued back and forth with my mother until her death on Christmas Eve ten years later.

1969 Canadian immigration laws weren’t nearly as restrictive as they are now. Back then, all I needed to reside in Canada was a letter from my prospective employer stating I was the best-qualified applicant for the position they were seeking to fill. As long as I had no criminal record, had a clean bill of health and presented my letter to the Canadian immigration officials at the Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario border crossing...that was about it. My family and I were issued Landed Immigrant cards and we rented a home in Chelmsford, Ontario which was a stone’s throw from Sudbury (population 90,535) and my new Ash Street employer CKSO-AM-FM-TV.

Chelmsford was primarily a French Canadian community and we soon became known as one of only a handful of Anglo’s in town. I went everywhere with my camera shooting pictures of everything French including the stop signs which read “ARRET!” How unusual and quaint I thought it all was and mailed the photos home to my parents in Chicago. I remember a ‘chip’ stand in Chelmsford and how different I thought it was to discover chips were actually French fries. But these chips came with gravy, something I’d never heard of in the U.S. I could also turn on my television set and watch programs in French. I had no idea what they were saying, but I found it fascinating just to watch. My first Canadian winter was spent in Chelmsford and that happened to be the year of a record snowfall for that area. The small subdivision where I lived was snowed under and it was several days before snowplows, which concentrated on the highways first, were able to clear the way. I had only been on the job for a few days when I found myself unable to leave my house because my car (by then a red Volkswagen) was unable to make it out of my subdivision onto the highway. To top it off, our supply of fuel oil was running out and the fuel truck was unable to get into the subdivision. To get some needed food supplies from a nearby store, I fashioned a long staff from a nearby tree and literally crawled over the deep snow to the highway. “Wow”, I thought to myself, “this Canadian living is rougher than I imagined!” I never saw that much snow again, but at the time I thought it was just another normal Canadian winter. My phone rang the first morning I was stranded and my news director at CKSO asked me to file several reports via telephone on what life was like for the residents of my stranded community. I did this for two days until the plows came. During this time, neighbours phoned to tell me their various ‘stranded stories’ and I got to be somewhat of a celebrity in that tiny town because of the notoriety I gave them. I worked as many of their names into my reports as I could. The townspeople embraced me fully after that, and the months I spent there before finding a place to live in Sudbury were pleasant and memorable.

Sudbury is the gateway to Northern Ontario and in the era of exploration, it lay just north of the major fur-trading route into Western Canada. The earliest recorded Indian habitation of the area is 6,000 to 7,000 BC, based on an excavation on nearby Manitoulin Island where quartzite tools and weapons were found. More recently, early Woodland Indians inhabited the area around 225 BC. From 1881 until 1885, the Canadian Pacific Railway worked to build the railway across the North with the first train arriving in Sudbury in late 1883. Sudbury became the railway’s regional headquarters. Two years later, the railway moved its headquarters. The Sudbury basin is the richest deposit of nickel ore in the world, and home to the International Nickel Company, or INCO for short. In 1883, ore with high levels of copper sulfites were discovered in the Sudbury Basin. In 1900, new methods for refining nickel were invented leading to the expansion of nickel mining in the area. INCO was formed in 1902 and incorporated under the laws of Canada in 1916. Expanding steadily over the decades, INCO added operations in Manitoba and, outside Canada, in the United Kingdom, the United States, Indonesia and other locations worldwide. Sudbury boomed during the First World War as demand soared and by 1921 with a population of 8,600, the Sudbury region became one of the ten largest communities in Canada. In the 1950s and 60s, environmental concerns were raised about the sulfur dioxide emissions from the smelting process, which so damaged the local landscape that NASA astronauts rehearsed their lunar landings in the area. These concerns led to the construction of the INCO Superstack in 1972 which dispersed the smelter’s emissions into the jet stream. I was a newsman at CKSO-AM-FM-TV during the period the astronauts trained in Sudbury and when what was billed as “One of the Tallest Smokestacks in the World” was constructed just off highway 17 at the western edge of town. Both of these events were giant news stories then and occupied the majority of our hours in the newsroom for quite some time. INCO remains one of the world’s leading producers of nickel and an important producer of copper, precious metals and cobalt. During my time in the mining town, the INCO Superstack was a must-see attraction for friends and relatives who visited me. So was the pouring of the slag .... the refuse from the smelting process. On many nights I treated friends to a view of the red-hot molten slag being poured from huge iron containers mounted on railway tracks. As the slag poured down the man-made hillsides of aged slag, the rough vesicular cindery lava lit up the night sky with a steamy warm red glow. Years of slag-pouring formed a landscape of barren black rock which created the aforementioned training ground for astronauts because the area was said to closely resemble the surface of the moon. Times have changed and environmentalists and ecologists have moved in to replant millions of trees and the region has regained much of its original greenness ... but during my years there from 1969 to 1974, the surroundings were indeed quite desolate. While the Superstack was the tourist mecca at that time, the famous giant INCO ‘Big Nickel’ now claims that honour. A turn off highway 17 takes you up a denuded hilltop to the attraction - exactly what it sounds like - a 30-foot-tall replica of a Canadian nickel and the entrance to the mine of the same name which has been turned into a museum. Here you can don a hard hat and descend 65-feet into this non-working exploratory mine as well as arrange guided tours of the INCO refinery.